Note: I am referring the original Marathi Ovi version of the Shri Sai Satcharita, beautifully translated by Mrs. Indira Kher. No copyright infringement is intended. These reflections and interpretations are drawn from my personal experience, devotion, and evolving understanding of Baba’s teachings and unceasing grace. I fully respect that others may hold different views or insights, and I welcome the diversity of devotion. However, I retain the creative and devotional agency to express myself freely on this blog, which is a heartfelt offering to my One and Only, Satchidananda Sadguru Sainath Maharaj of Shirdi.

With Love, Priyanka

This reflection deals with the story of the author being addressed as “Hemadpant” by Baba. And as we all know, nothing is ever meaningless when it comes to Him. Baba spoke little, but whenever He did, His words carried immense depth. When Baba referred to “expositions of the two contrary viewpoints,” the author was left pondering over it. In his writing, Hemadpant ji also mentions the ṣoḍaśa saṃskāras, the sixteen Hindu purificatory rites. These rituals sanctify life from conception to death, reminding us that every stage of human life is sacred and meant for self-realization. Among them, the nāmakaraṇa (naming ceremony) is well known. Interestingly, some Gṛhya Sūtras like the Hiranyakesi Grihya Sutra prescribe two names for the child, a common name (vyavahāra-nāma) for the world and a secret name (rahasya-nāma) known only to the parents, meant for ritual use and protection. Many traditions change or add names at initiation. In Tantric and yogic traditions, a dīkṣā-nāma given by the Guru becomes a second, inner identity. In Vaishnava lineages, devotees are given spiritual names, while in Christianity baptism often confers a new name. The principle remains the same I believe, names carry power, and a Guru-given or hidden name anchors the soul to its highest reality.

Most of us today do not have a second name, but perhaps one way to reclaim this practice is to adopt a name inwardly that resonates deeply, even something as simple as adding “Sai” before our own. This is my personal energetic understanding. Which is why this moment in the Satcharita is so moving, Baba Himself performed the nāmakaraṇa for the author. An initiation of sorts and if you have read Satcharita, you’ll observe how He gave rarely called anyone with their name for eg. langda kaka for Shri Hari Sitaram Dixit, Nana for Shri Narayan Govind Chandorkar, Radhakrishni for Mai whose real name was Sunderabai Kshirsagar and many more we will come across as we read other chapters. To be given a name by the Sadguru is no small blessing. How fortunate Hemadpant ji was to receive such grace directly from Baba.

In the previous reflection, we saw the ovi in which Baba makes it clear that argumentative behaviour is futile and unnecessary. Now the author, after admitting how ignorant and prideful he had been in engaging in idle talk, arguments, and debates, confesses that he was really far from true wisdom. And isn’t that true for so many of us? Only a mind caught in pride and insecurity feels the need to fight and argue. I know I have found myself in this trap many times. Most of us debate only to prove ourselves right and the other wrong. I have done this often in my own life, until one day I realised how truly useless it is to argue with someone who is so full of their own opinion that there is no space even to receive another’s words, let alone to understand them. It is exhausting, sometimes even headache-inducing. At such moments, I ask myself, “would I rather waste energy in arguments, or focus on my own progress and turn inward to Baba?” More often than not, it is wiser to leave the table where my opinion is not respected. Arguments are not only a waste of time and energy, they can also trigger negativity and lodge in the subconscious as painful memories. Of course, we can be wrong too, and healthy discussions are part of growth, but debates should not turn into battles, especially in spirituality, where there is no one-size-fits-all. Only Guru or God knows what is best for each soul.

When we insist on dictating what another person must do, we are subconsciously playing God. And I once heard a teacher say, “thinking you can play God is the greatest form of doer-ship.” Baba has asked His devotees again and again to drop all sense of doer-ship. This does not come naturally because we have been conditioned since our birth to consider ourselves to be this body, but it is something we must practice with mindfulness, until surrender replaces the compulsion to control. Even after years of practice, I found myself defensive and reactive, like a timebomb. It was only about a month ago that I saw clearly the root of it all: fear. At the heart of our reactivity is fear. Fear of being abused, abandoned, disrespected, or made to feel small. To protect ourselves from these possibilities, we develop defense mechanisms and forget our true state, which is love.

We worry that if we don’t rehearse our responses beforehand, the next situation might hurt us or diminish us. The tragic part is that the other person is also conditioned and wounded in the same way, defending themselves against their own fears. This is why it becomes so hard to be vulnerable, we don’t believe we can be loved unconditionally. And so, we withhold, while forgetting that the one in front of us also carries wounds they are trying to guard. This is why it is so important to deal with deep-rooted fear and insecurity, the aching need for love and acceptance that we expect from others. Of course, arrogance and ego play their part too, as they are also products of conditioning. But as devotees, our task is not to blame, it is to look deeper, to understand the root of the problem. And the truth is, no one can ever love us unconditionally unless they have learned to love themselves that way. Which means it is pointless to set such expectations on others. And same goes for you.

Instead, place your expectations only on Baba. He is the one who is willing to walk a hundred steps toward you when you walk even ten. With Him, you will feel liberated. Baba loves us unconditionally, truly, and deeply. And when you see yourself through His eyes, you begin to recognise how profoundly special you are to Him. Love yourself like He loves you. Anyway, it is only silence that truly exists. Every single thing, whether thoughts, words, or actions, is just noise in the grand scheme of things. As the Tao Te Ching says, “The Tao that can be spoken is not the eternal Tao.” This is why most saints spoke very little. Baba, Bhagavan Nityananda, Sri Ramana Maharshi, even the Mother, none of them wasted words, because words distort direct experience, I feel.

At best, we can translate only a fraction of our emotions and insights into words, and even then, the listener filters it through their own conditioning, upbringing, and level of understanding. As someone who often speaks a lot with those I love, I have learned how easily words lose their meaning when used in excess. This is why I consciously try to speak less. The same is true of actions. When actions go unchecked, they harden into behaviours. Behaviours repeated over time become patterns, and patterns are notoriously difficult to break. We carry them across lifetimes, doing everything we can to justify them. So here, when Baba calls Hemadpant ji out, He is not simply pointing to idle talk or argument. He is addressing a much deeper issue that lives in all of us. That is what initiation through a Guru truly is right? The peeling back of all layers, all lint and residue, until only the root is revealed.

Hemadpant ji was gently persuaded by kaka and nana to go to Shirdi, the very urging that set him on the path. You, my dear reader, occupy that same place for me now, because we all share one father, one Baba, and it is often another’s nudge that opens the door. Hemadpant ji admits there must have been a rinanubandh at work, as I noted in my introduction, those who come are called by Baba’s will. He tells us how doubts beset him on the day he prepared to leave as a friend’s young son fell ill. All remedies were tried, the guru sat beside the child, yet the child died. Hemadpant ji sat with karma, destiny, and the huge question that death always brings. Death strips pretence away. Yudhisthira replied to Yama at the gates of heaven, what is most striking is how people live as if they will never die. Confronted with fragility of life, Hemadpant ji felt that sharp detachment many of us have felt after hearing of tragedies or losses. In those moments the ego’s palace, the false importance or sheesh-mahal we have built around ourselves, shatters, and we are left bare and strangely free.

This incident weakened Hemadpant ji’s resolve to visit Shirdi. He thought, “If something is destined to happen, it will, so what need is there for a Guru?” He was not entirely wrong, don’t we also often slip into such thinking? This is what is called being a fatalist, believing that everything is predetermined and that our efforts, choices, or relationships make no difference. And many times, we drift even further into nihilism, feeling that nothing has meaning and nothing can save us. But I believe this is only until we have had a tryst with grace. For grace is so magical that it can overturn anything. Even when Hemadpant ji was dejected, grace had already started working in his life. At that time, Nana Saheb, who was on his way to Bassein, instead went to Bandra and called on the author, gently enquiring about his slackness in visiting Shirdi. Eventually, Nana left for Thane, and the author finally decided to pack his belongings and set out. Yet even then, he boarded the wrong train.

But since Baba had now resolved to call His beloved devotee to Himself, He appeared in the form of a Muslim gentleman who alerted Hemadpant ji, explained the route of the train, and guided him to the correct one right at the start. Had this not happened, the author might have lost the resolve to visit altogether. And this is Baba’s way. He always guides us back to the right path. All we have to do is remain willing to heed His signs and His advice. While writing this I feel as if I am journeying with the author back to 1910. My chest tightens and tears rise because I wish I could have seen it with my own eyes. The next day he was greeted by Bhausaheb Dixit and arrived just in time to receive Baba’s darshan around nine or ten o’clock. He was guided by Tatyasaheb Nulkar, who was returning from Dwarkamai for the dhool-bhet pilgrims offer on arrival, a humble rite of greeting where one sprinkles dust or offers reverent salutations at the saint’s feet as a sign of devotion and utter surrender, because Baba was soon to set out for Lendi Baug. I can only imagine the swell of longing and relief in his heart.

I would not have been able to hold back my tears either. The first sight of the Master is beyond language, books and stories prepare you, but they do not deliver the visceral opening of the heart that happens when you see Him. I remember my own first darshan in Shirdi: for an hour I could not stop crying, as if a tap had opened and the years of holding had finally released. I stood close, and people tried to crowd me away, yet later I realised that the exact spot where I had stood was strange and intimate, his eyes had looked right at me. An aunty behind me laid her hand on my head and said, “Don’t cry, all will be well,” while I knew, in my bones, I was crying because everything was already, finally, well. All the senses quieted, my eyes could not be satisfied with that one look. That is the feeling Hemadpant ji must have felt, seeing Baba moving, speaking, present in the world, an encounter that overturns the ordinary and leaves the heart forever altered.

Hemadpant ji thanks those who helped him in his spiritual progress, calling them his true kith and kin, his real relatives. Over the years, I have found this to be the truest of truths. The one who walks with you toward your real state, your true abode, is the real friend. Anyone who drags you deeper into Maya is nothing but an instrument of Maya itself. It is important to disassociate from such company, even if it means stepping back from those closest to you if they are fully immersed in ego and illusion. But remember, do not blame or criticise them. It is simply not their time to awaken. And never try to wake them yourself, you are not God, and it is not your duty. Waris Shah says, “Dukhi jāge dukh de kāraṇ, sukhi na jāge koi; lagī binā rain na jāge koi.” A person awakens only through sorrow, no one truly awakens in comfort. Without the fire of longing (lagī), even the long night of life passes in sleep but suffering shakes us awake, it unsettles our illusions, stirs yearning, and pushes us to seek what lies beyond pleasure and pain. Joy rarely calls us inward, but sorrow often becomes the spark that turns us toward grace. I speak this from experience.

In the presence of the field of pure Source, your vibration naturally rises. The same happened with Hemadpant ji. After his first darshan of Baba, he felt his karmas, those which keep us bound in the dualities of pleasure and pain, right and wrong, success and failure, virtue and sin, suffering and adversity, doubt and pride, were dissolved. Baba was the Source itself. And here, in these verses, we see how the mere sight of Him could transmute the heavy karmas of a devotee into joy, peace, and purity.

How fortunate was Hemadpant ji, and all of us, to have the Manas Sarovar, Baba to transform us into our best selves. Yet, as human nature is, on the very first day he found himself in an argument with Balasaheb Bhate on the old question of destiny versus free will. The author had not yet surrendered fully, so he argued that one should live with agency and independence, doing one’s duty without relying on a Guru. The opposing view, however, was that no matter how much you study or strive, nothing truly brings deliverance except the Guru’s grace. This debate is as old as time. In my own view, I do not believe in free will. If you read Ramavijaya, you will see how every event, good or bad, unfolds exactly as destined, according to the will of Shri Hari. This shows that while Hemadpant ji had experienced some detachment, a complete transformation had not yet taken place. And isn’t this the case with all of us? We keep making efforts, correcting ourselves, measuring, comparing, and then blaming fate when things do not work out.

The truth is, according to me of course, our duty is to give our best effort and then surrender the result to the Guru. If it is meant to happen, it will happen in the best possible way when offered at His feet. If not, it was never meant to be. Purusharth (self-effort) certainly matters, but the idea that “I alone am the doer” is nothing but arrogance. Without His will, we cannot even lift a finger. As Krishna says in the Bhagavad Gita (18.14–16), every action has five causes: the body, the doer, the instruments, various efforts, and the will of the Divine. One who sees the Self as the sole doer is deluded, for without the Supreme sanction no action is possible.

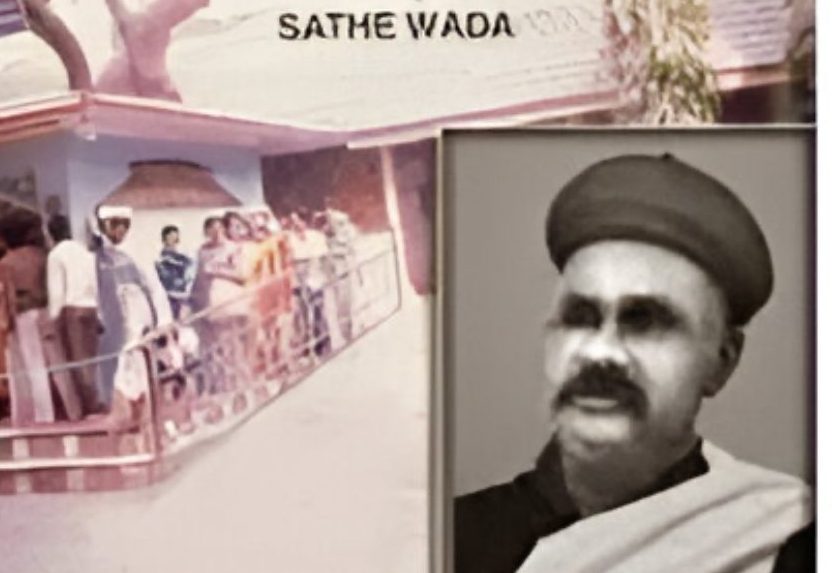

After his inconclusive arguments, when the author went to Dwarkamai, Baba asked Kaka about the happenings in Sathe Wada, the only lodging available for pilgrims at that time and then, quite significantly, referred to the author as “Hemadpant.” Who was Hemadri Pant? He was a polymath, a statesman and minister to the Yadava kings, sharing court with luminaries like Pandit Bopadev. Hemadri authored Dharmashastra texts, composed codes of conduct aligned with the Shrutis and Smritis, and wrote extensively on politics, religion, pilgrimages, charity, and moksha. He was also a great poet, remembered for works like Lekhan Kalpataru. He was contemporary to saints such as Namdev, Jnaneshwar, Nivrittinath etc. When Baba gave this name, the author felt small and undeserving in comparison to such a towering figure, which was precisely Baba’s intention, to strike at his ego. And yet, as we know, in the future Hemadpant ji went on to write our very life manual, the Satcharita, which covers many of these same subjects, and even later took charge of accounts for the Sansthan. This shows us how Baba both humbled and empowered him.

Humility is essential for every seeker, but even more so for one entrusted with a great purpose. The Guru must always be seen as supreme. If Lord Rama and Krishna themselves bowed before their Gurus, who are we to imagine otherwise? As the author says, without the Guru there is no true knowledge and no deliverance. The pride of knowledge must end. One must empty the cup, erase the divisions of “you and me,” “this and that.”

Swami Nityananda, in the very first verse of the Chidakasha Gita, says:

“Jnanis are mindless. To Jnanis, all are the same. They have no slumber, no dreams, nor sleep. They are always in sleep. The sun and the moon are the same to them. To them, it is always sunrise. The glass of a chimney lamp, when covered with carbon, is not transparent. Similarly, the carbon of the mind should be removed.”

Dear devotee, always remember, after all, everything we think we “know” has come from the conditioned mind. True wisdom begins when the carbon is cleared, and only the light of the Self shines. And there is no better way to realise that than living the teachings of Baba and devoting your mind, body and soul to Him.

|| OM SAI SHRI SAI JAI JAI SAI ||

|| SHRI SATCHIDANANDA SADGURU SAINATH MAHARAJ KI JAI ||

Note: Since the chapters are long and stretch across many ovis, I will be breaking them down in a way that allows us to go deep without losing track. Each reflection will cover either a single concept, a leela, or at most 50 ovis – whichever completes a thought fully. This way, we can sit with every aspect of the Satcharita as carefully and reverently as possible, without skipping a single detail, guided always by Baba’s grace. I’ve also chosen this approach because very long posts can feel heavy or overwhelming for some devotees. Keeping them snack-able and focused will hopefully make it easier for everyone to read, return to, and reflect on in their own pace. All rights reserved.

Leave a comment